One of the most tiresome arguments that I have seen play out in Christian circles is about judging other people’s sins. There are a number of clear prohibitions in the Bible about judging other people’s sins, but often Christians feel compelled to dilute this teaching due to “practical” considerations. We say that it is necessary to “hold people accountable”, or to “affirm God’s moral law”. According to this logic, to not judge people at all is to succumb to “moral relativism”.

Often the conclusion to this argument is that it is appropriate to judge other people’s sin, as long as the judgment is “appropriate”. This has always seemed to me a rather worthless qualifier. After all, everyone who passes judgment on another thinks the judgment is “appropriate”!

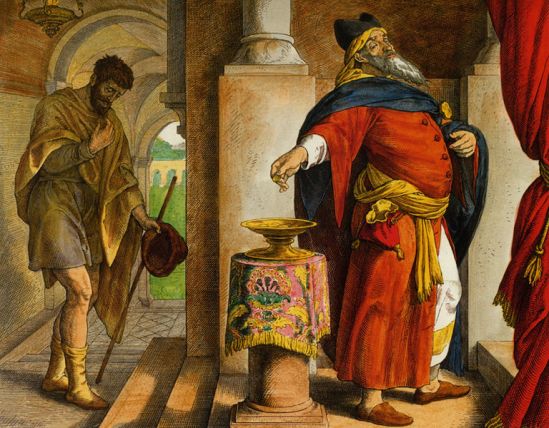

A message that comes through loud and clear in the Orthodox lenten season is a prohibition against judging. The services of the Lenten Triodion (the lent liturgy book) begin with the Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee, which focuses on Luke 18:10-14:

Two men went up to the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. The Pharisee stood by himself and prayed: ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other people—robbers, evildoers, adulterers—or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week and give a tenth of all I get.’

“But the tax collector stood at a distance. He would not even look up to heaven, but beat his breast and said, ‘God, have mercy on me, a sinner.’

“I tell you that this man, rather than the other, went home justified before God. For all those who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.”

We also say this prayer of St. Ephraim the Syrian in our morning prayers all throughout Lent. This prayer ends with these powerful line, spoken twice:

Yea, O Lord and King, grant me to see mine own sins and not to judge my brother.

Every Sunday (even outside of Lent) we read this pre-communion prayer of St. John Chrysostom. It begins as follows:

I believe, O Lord, and I confess that thou art truly the Christ, the Son of the living God, who didst come into the world to save sinners, of whom I am chief…

So every time I participate in the Sunday liturgy I declare myself “the chief of sinners”. Is this literally true? How do I answer that? How can I speculate on the spiritual state of another person? But if St. Paul can call himself the “chief of sinners” (1 Tim 1:15) then so can I.

These liturgical elements hint at the reason why judging is dangerous. In Orthodox Christianity, we think of salvation not just as a moment in the past, but also in the present tense as a process of restoration, of a continual turning away from sin and towards God. The proper response to hearing the Gospel should be a revulsion at our own wickedness, and a desire to repent. What folly it is to look at the word of God and decide instead that it proclaims oneself righteous and condemns other people!

We learn a lot about the dangers of judging others in the words and deeds of early Christians, particularly the desert fathers and mothers. One very celebrated story is that of St. Moses the Ethiopian:

A brother at Scetis committed a fault. A council was called to which Abba Moses was invited, but he refused to go to it. Then the priest sent someone to say to him, ‘Come, for everyone is waiting for you.’ So he got up and went. He took a leaking jug, filled it with water and carried it with him. The others came out to meet him and said to him, ‘What is this, Father?’ The old man said to them, ‘My sins run out behind me, and I do not see them, and today I am coming to judge the errors of another.’ When they heard that they said no more to the brother but forgave him.

There are also several warnings against judgment that affirm James 4:12, “There is only one lawgiver and judge, he who is able to save and to destroy. But who are you to judge your neighbor?” Consider this celebrated story about the desert fathers is that of St. Isaac the Theban:

An angel appeared before Isaac and presented before him the soul of someone who had just died. “Here is the soul of a person you have judged,” said the angel. “Where do you order him to be put, into the Kingdom or into eternal punishment? Since you want to judge the just and the unjust, what do you command for this poor soul?”

Frightened beyond measure, Isaac spent the rest of his life praying with sighs and tears to be forgiven of this sin. He had seen the seriousness of judging another.

Abba Macarius went one day to Abba Pachomius of Tabennisi. Pachomius asked him, ‘When brothers do not submit to the rule, is it right to correct them?’ Abba Macarius said to him, ‘Correct and judge justly those who are subject to you, but judge no one else .